Transcending—Art into Poetry

During a recent workshop with the poet Susan Rich, on Ekphrastic poetry––which is poetry that explores art––at La Conner’s gallery/museum, MoNA, I became entranced with a painting, which I’ll share in a minute. Susan inspired us to find a painting or piece of art in the gallery, and using a rhetorical device known as ekphrasis, engage with the painting, drawing, sculpture, or other mode of visual art.

The term ekphrastic (also spelled ecphrastic) originates from a Greek expression for description. The earliest ekphrastic poems were vivid accounts of real or imagined scenes when writers in ancient Greece aspired to transform the visual into the verbal. Later poets pushed beyond depiction to reflect on deeper meanings. Today, the word ekphrastic can refer to any literary response to a non-literary work.

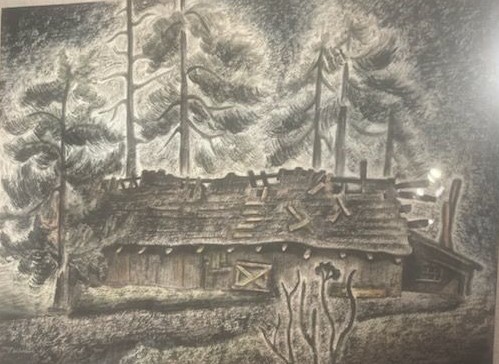

The painting that grabbed my attention and heart was The Longhouse by Helmi Juvonen, a gift from Wesley Wehr.

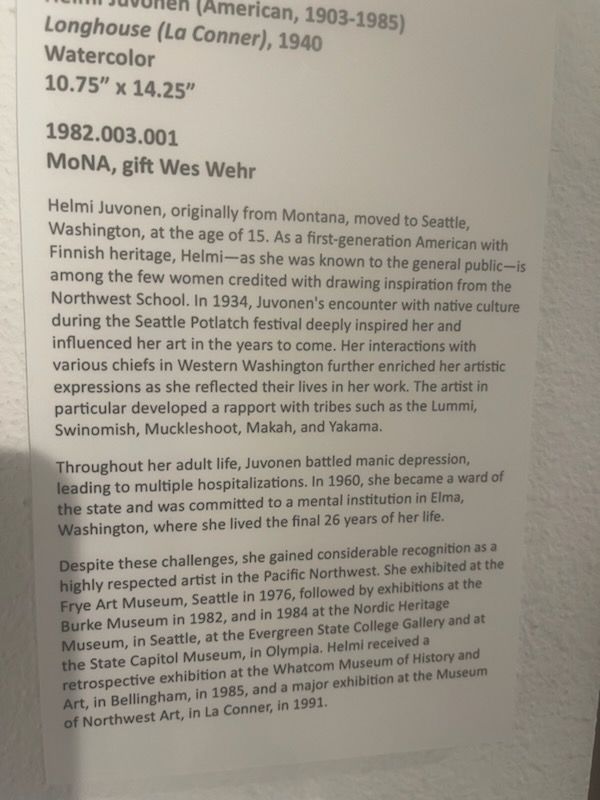

Helmi Dagmar Juvonen (January 17, 1903 – October 17, 1985) was born to Finnish immigrants (Helmi is Finnish for Pearl) and became an American artist associated with the artists of the Northwest School, and was active in the Seattle, Washington area.

She attended Queen Anne High School, and after graduating, worked various art and design-related jobs while studying illustration, portraiture, and life drawing with private teachers. In 1929 she received a scholarship to Cornish College of the Arts, where she studied illustration with Walter Reese, puppetry with Richard Odlin, and lithography with Emilio Amero. You can read more about her illustrious career here.

Sadly, Helmi was diagnosed with schizophrenia (manic-depression), and was committed to a mental institution in Elma, Washington, where she spent the final 26 years of her life. There, she was visited by artists and supporters, who facilitated wide recognition for her work, during her lifetime through many art museum exhibitions.

Helmi transcended boundaries

Native American culture cultivated Helmi’s creative spirit and empowered her to transcend the boundaries of ordinary life, poverty, and decades in a mental asylum. Her interest in identifying the origins of human culture, especially as it addressed the dichotomies of good and evil, led her to investigate these themes in diverse spiritual traditions – Judeo-Christian, Tibetan Buddhism, and the Baha’i faith.

And in the painting that captured me so completely, I sensed something beyond the brokenness of the exterior. Combined with my (limited) knowledge of native folklore from the Oregon Coast––gleaned while researching my novel Return To Sender––and reading a bit about the Lummi Nation (Pacific Northwest myths, I wrote the essence of what I felt and saw in this piece of art.

My poem from that day, which is also published on the MoNA website, is titled, Dancing with the Dead. Please visit MoNA’s site and explore all the poems produced that day. I have a 2nd poem on their site titled, Shadow Dance.

Dancing with the Dead

By Mindy Meyers-Halleck

Her house is ill,

they said.

Unhinged shutters,

band aids on the roof,

boards as exposed as skeleton bones,

a crooked door that’s lost its will,

and a roofline of sagging skin.

Her house is ill,

and it allows no one out,

and no one in.

The native peoples

said of their treasured mad woman

with skin white as pearl

that she is

broken in the head.

––but, that sacred wound,

They said,

allows darkness to seep in.

And in those spirit-filled shadows

she dances with the dead.

It took her a lifetime,

to embrace the brokenness in her head––

––her dark shadow sister who never saw the sun––

A sister coiled in nocturnal corners, dreaming of

wolves, trees, and danger

she was never able to outrun.

The trees that surround her house are

not quite alive

not quite dead,

they haunt the yard

––redolent with tears and blood of the fallen

sister who never saw the sun.

She is broken in the head,

they said.

In those mist shrouded trees

she sees

The Keeper of Drowned Souls.

His green long-fingered hand,

spindly as spider legs,

beckons her to follow

deep, deeper into the hollow.

The Keeper of Drowned Souls exists

transitory between the human world and the phantom world

he tells her,

her dark sister who coils like the snake

inside her house,

is condemned to endless hunger, agony, wandering and sin.

Because her house is ill,

it allows no one out,

yet he wants in.

She is broken in the head,

they said.

She observes ethereal phantoms,

and dances with the dead.

October 19, 2024 at 10:15 pm

Great work Mindy! I’m anxious to read more.

LikeLike

October 20, 2024 at 2:24 am

Thank you!

LikeLike

October 20, 2024 at 3:35 am

A fascinating post, Mindy. Your poem gathered it all in–the painting, Helmi, native American culture, bodily illness and mental illness. I especially like the first stanza.

LikeLike

October 21, 2024 at 3:51 pm

Thank you, She was fascinating. I appreciate your feedback. Cheers

LikeLike

October 23, 2024 at 6:14 pm

Mindy, I really enjoyed and was moved by your poem! Very nice work! I finished my autobiography and published it on Amazon. “The Art of Refuge” I wish you were teaching a class again. I thank God for you! Steve

LikeLiked by 1 person

October 23, 2024 at 7:41 pm

Oh My! Congratulations. And thank you for your kind words.

LikeLike