love

Mama Told Me Not To Come

Yesterday, while writing in a coffee shop, a stranger decided to join me. Despite my suggestive glance at the room full of unoccupied tables, she plopped down at mine. “You’re a writer,” she said. And then she proceeded to interview me about the who, what, when, and where that inspired my newly completed (not yet published) novel…. I got over my annoyance and had an interesting conversation, which ultimately inspired this blog post and future posts. I explained to my curious new friend ….

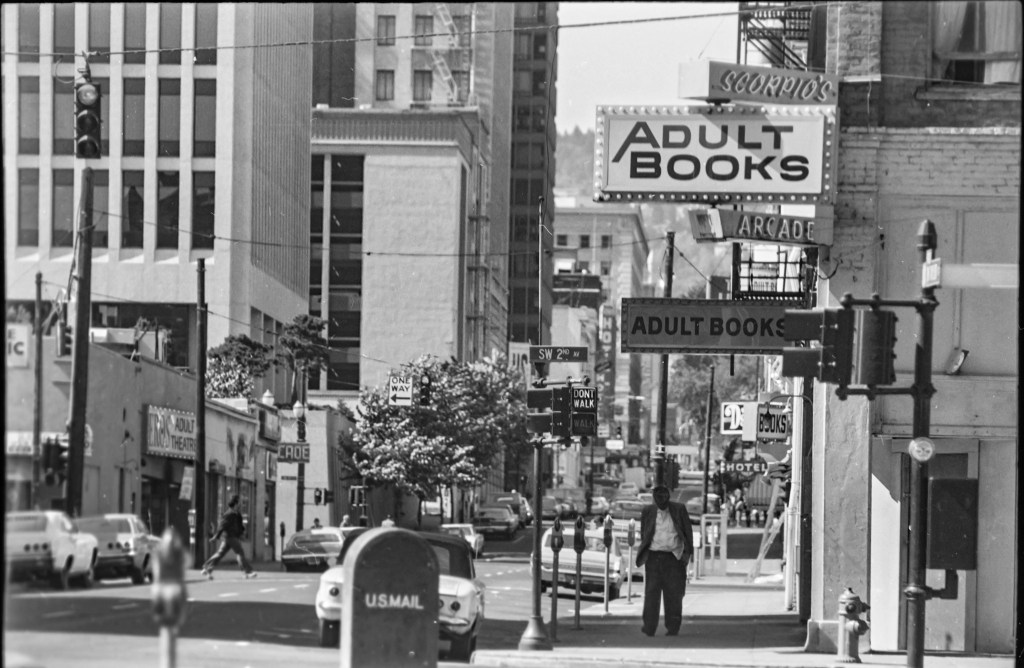

In 1970s, Portland, Oregon, when stagflation met disco-mania, Portlanders seeking liberation from urban blight, lights out orders, and ambushed pipe dreams turned to sexploitation. Mary’s Club, which features prominently in my newly completed novel, and other strip joints packed in customers. X-rated theaters and bookstores of the ADULT sort exploded around the city.

It was a boom era fueled by relaxed obscenity regulations that led to porn palaces and live performances that ruled the neon landscape. Ultimately, The Oregonian Newspaper, where my grandfather worked, named Portland “the pornography capital of the West Coast.”

Religious cults, Vietnam protesters, and abortion rights activists heralded signs on every street.

The day before my fifteenth birthday, Grandpa pulled me aside at the Oregonian. “A lot of things aren’t making it into the paper,” he said in a solemn tone. “We got crooked cops, racketeers, editors on the take,” he whispered. “Pretty girls like you are in danger.”

He explained in one wide-ranging account how girls my age were easy prey, often collateral damage in a metropolis run by the mob. And how Portland’s corrupt politicians had earned a new moniker for The City of Roses; the vice capital of the northwest. Police corruption extended further than pacifying Teamsters on the docks; it was citywide. The thriving narcotics trade enticed officers to look the other way while their palms were greased and young girls vanished from the streets.

Grandpa never spoke to me about such shocking (to my naive sensibilities) issues. So, I listened.

Planted deep within grandpa’s warning that day were the seeds of my novel, Beyond This Wicked Realm to follow some fifty years later. For which I am seeking representation.

Grandpa made sure I had a bus pass, a library card, and books; the classics on which he expected a verbal book report. In his way, he was making sure his teenage granddaughter was too busy to go looking for trouble. Nonetheless, trouble was around every corner looking for her.

After school, a couple of days a week I worked for my dad in downtown Portland, just a few blocks from the Oregonian. I rode the bus into the city past businesses with handwritten signs in dark windows (victims of the governor’s lights-out orders), gas stations with NO GAS signs at the curb, hippies sleeping on park benches, and the yeasty smell of the Henry Weinhard Brewery that permeated everything. I leaned my head against the bus window and studied the girls walking up and down Broadway and Burnside. Some were my age, even younger; black fishnet stockings, black raccoon eyes, and faux fur cropped sweaters, sashaying down the streets, unsteady on their platform shoes. At ten in the morning, they already looked like they had been out partying and drinking all night. Maybe they had. I didn’t know. My grandma called them the lost girls. All I knew was that I never wanted to get lost.

One day when I got off the bus, as I hurried through a group of shouting Vietnam War protestors, a man grabbed me. He had an Afro the size of a beach ball, wore a long black leather coat, and dark glasses. He towered over me. At first, I thought he was one of the Black Panthers, though they normally weren’t in that part of the city. I was terrified. I didn’t speak.

Then he let go of my arm and said, “Hey foxy mama, you a stone fox.” He looked me up and down.

My eyes burned with tears, but I stood paralyzed.

“We could make some moolah,” he said, rubbing his fingers together.

But then, a woman who looked to be my mom’s age slammed his head with her protest sign and shouted, “PIMP! Leave that child alone.” When she did that, a group of protesters ran over to us, shouting, “Police … PIMP!”

That woman turned to me and said, “Honey, you should run now.”

Like Forest Gump, I bolted and ran all the way from 3rd and Washington to 11th, without looking back or stopping for traffic. People honked and shouted, but I didn’t care. I ran to the safety of my dad’s shoe repair shop on 11th. I never told Dad why I was out of breath and crying that day. He gave me a cup of tea and suggested I go read my book in the back of the shop for a while. He no doubt figured it was ‘that time of the month.’ It wasn’t.

It was the first time I was ‘approached’ by a pimp, but it wouldn’t be the last. They were on every corner trying to recruit girls for strip clubs, and worse, much worse. One day, when I left the Multnomah Library on 10th street, carrying my homework books, a man in a black car at the curb offered me three hundred dollars––in today’s money that’s over $2000.00–– to dance in a cage that would be hanging from a ceiling in a local nightclub. I backed away, turned, and ran like that protestor woman told me to do. I wasn’t going to freeze and cry again. I ran.

Being a teenage girl in 1970s Portland was like being a gazelle pursued on an open tundra to the soundtrack of Three Dog Night’s, Mama Told Me (Not to Come). I learned to run, hide, seek shelter, and NEVER talk to men in parked cars at the curb.

I had a few safe havens, good people around me, shelter, and some good sense handed to me by my family. I survived, but many didn’t.

I wrote this novel for them, the lost girls, those who didn’t make it out and those who did make it through the darkness to the other side.

This is the environment for my current novel, titled Beyond This Wicked Realm–In 1973, four women—a Holocaust survivor, a mobster’s daughter, a drug dealer’s abused girlfriend, and a lady-scholar turned drifter—form an unlikely sisterhood in a fight for survival against Portland’s illicit porn and drug trades.

That highlights some of the backdrop for my novel. In an upcoming post I will share my characters, women I’ve grown to love, mentors I wish I’d had, and lost girls I knew.

Themes in fiction (or Non) Writing

All stories have themes – whether they’re intentionally explored or bubbling under the surface – and the exploration of different themes adds layers and depth to any story, especially if those themes are universal, tapping into what Carl Jung called, the collective unconscious.

The other day I mentioned to a class I was teaching, that discovering what your theme is not only helps you tell the story, it keeps you on track. For example in my novel, Return To Sender, I tried to keep only the letters my protagonist, Theo wrote from war (Korean) that had to do with saving someone. Why? Because he wants to be saved. Redemption is the theme.

I didn’t abandon the theme when I revealed his letters, but instead used them to support the theme. This excerpt from his letters is an example;

It rained hard the night we evacuated the children from their orphanage, harder than I’d seen, even on the Oregon Coast. The smell of wet dirt, trees, and napalm, that’s the smell I remembered most, the chemical and petroleum of burning napalm. We scrambled with the kids up Korea’s dominating T’aebaek Mountain—the mountain was nearly the same height as Neahkahnie but had limestone caves tunneled deep within. Massive stalagmites hung heavy throughout the corridors. Ancient bamboo-roped bridges built across chasms linked the vast rooms of the caves to one another. It was otherworldly. But the surviving nun knew the place, the Karst Caves, and said we’d be safe. Water spouted from innumerable cracks and seeps – the sound of rain and falling water was everywhere.

It rained hard the night we evacuated the children from their orphanage, harder than I’d seen, even on the Oregon Coast. The smell of wet dirt, trees, and napalm, that’s the smell I remembered most, the chemical and petroleum of burning napalm. We scrambled with the kids up Korea’s dominating T’aebaek Mountain—the mountain was nearly the same height as Neahkahnie but had limestone caves tunneled deep within. Massive stalagmites hung heavy throughout the corridors. Ancient bamboo-roped bridges built across chasms linked the vast rooms of the caves to one another. It was otherworldly. But the surviving nun knew the place, the Karst Caves, and said we’d be safe. Water spouted from innumerable cracks and seeps – the sound of rain and falling water was everywhere.

We clawed our way up the hills and out of the valley of death. The CCF had entered the war that week and were as ubiquitous as the rain. The NK were ruthless and bloodthirsty and wanted those kids—and now us—dead. The kids and that dedicated nun were too vulnerable for us to abandon for slaughter, so we, my buddy Lieutenant Peters and me, abandoned our orders instead.

Sometimes we writers aren’t fully aware what our theme is until we write a good bit of the story, set it aside, let it ruminate in a drawer for a day, ten or 30, then read it. The theme(s) should emerge, jump off the page, even sometimes, surprise you. Then when you rewrite and edit you can shore them up and explore them in more satisfying (to both you and your readers) ways throughout the story.

There are tons of themes, and in a story of any length, there’s generally more than one. Death, War, Prejudice, Freedom…and it shouldn’t be a shocker that the number one theme in literature is love. It’s one of the most prevalent topics in books, movies and music. Love is a universal, a multi-faceted theme that’s been examined in a number of ways throughout storytelling history.

Puppy love, unrequited love, first love, lost love, forbidden love, married love, the love between parents and children, siblings, friends, pets… the power of love to triumph over all…except when it doesn’t.

What are some different love theme examples in literature?

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is a tragic tale of forbidden love with dreadful consequences.

Pride and Prejudice explores the type of love that develops slowly over time, from misunderstanding and disdain to friendship, respect and love.

Wuthering Heights explores love by emphasizing how its passion has the power to unsettle and even destroy every unfortunate life in its path.

To create more layered tales, explore themes in your writing.

Leave a comment